Attractions

The Old West Town:

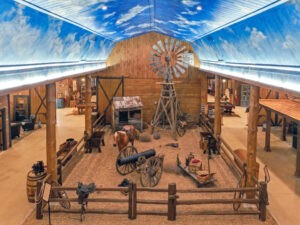

The center of our Old West Town was reproduced directly from 1800s photos of real towns, capturing the look and feel of a time when dusty roads, horse-drawn wagons, and wooden storefronts lined the horizon. It’s bordered by split rail fencing, giving structure and authenticity to the space, while stamped brick concrete walkways connect the east and west sides—replicating the worn footpaths used by townsfolk, tradesmen, and travelers.

Scattered throughout are vintage antiques and other rustic props that set the scene for unforgettable photos and unforgettable memories. Wooden benches line both sides of the street, inviting guests to sit, relax, and soak in the atmosphere, adding a layer of wonder and ambiance.

Recreating our Old West Town has been a true labor of love—one that’s taken years of dedication, passion, and acute attention to detail. Every building, artifact, and display has been carefully curated to reflect life in the 1800s as authentically as possible. It’s more than a setting—it’s a moment frozen in time, and it’s all waiting for you to discover!

All around you, vivid life-size scenes unfold:

Overhead, a hand-painted ceiling sets the scene, enhanced by special ceiling optics that gently shift from bright midday sun to starlit night, placing you in the full rhythm of an old Western day. As the lighting changes, you’ll feel the transition from buzzing frontier afternoon to the calm hush of a prairie night.

Along the street are hitching posts, saddles, watering troughs, and even real tumbleweed, shipped directly from the West, to enhance the texture and depth of the environment.

A Snake Oil salesman stands proudly beside his decorative buggy, ready to pitch his latest miracle cure.

An 1800s-style water tower and wooden windmill rise tall above the town, timeless symbols of survival and self-reliance. You’ll spot a weathered ammo shack, a replica cannon, and wagon wheels propped against fences—all authentic to the frontier era.

Dressed in authentic period clothing, we’ve placed realistic-looking mannequins throughout the scene, custom-crafted to resemble 1800’s townspeople. These figures bring warmth and movement to the town—from the saloon girls and shopkeepers to cowboys and train passengers, frozen in moments that tell the story of this transformational era.

Whether you’re sitting on a custom bench or leaning against one of the many vintage trunks, you’ll feel like you’re waiting for the next train into town, surrounded by the bustle of western life. Every detail is designed to transport you—step by step—into the vibrant, gritty, and unforgettable world of the American Old West.

The Wells Fargo Stagecoach:

Because these stagecoaches carried such high-value cargo, including gold and payroll, they quickly became prized targets for outlaws and desperadoes. Between 1870 and 1884, an estimated 347 stagecoach robberies were attempted or successfully carried out. In response, Wells Fargo began placing armed guards on board—giving rise to the iconic phrase “riding shotgun.”

Wells Fargo grew rapidly, acquiring competing express companies and even operating portions of the famed Pony Express. In 1872, they struck a deal to run express services along the expanding Transcontinental Railroad. As the iron rails reached farther across the country, reliance on stagecoaches declined. Yet stage lines remained vital in connecting remote communities to the rail hubs well into the early 20th century.

More than just mail carriers, stagecoaches served as the fastest and safest means of long-distance travel across the rugged frontier. They transported passengers, goods, and the promise of civilization into the untamed West.

The stagecoach featured here is a finely crafted, fully functional reproduction of a classic Wells Fargo coach—built in the spirit and style of the originals. Constructed primarily from sturdy oak, it’s outfitted with iron mountings, finished in black enamel, and suspended on traditional leather thorough braces—an ingenious early form of shock absorption.

The coach proudly bears the markings “U.S. MAIL” beneath the driver’s seat and “WELLS, FARGO & COMPANY” along the upper panels of both sides. It comes equipped with two yokes and a rooftop luggage rack complete with period-style baggage—offering a striking and authentic visual straight out of the 1800s.

Though Wells Fargo’s reign over the stagecoach era was brief—lasting just a few years from 1866 until the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869—their legacy endures. The final spike was driven at Promontory Summit, Utah Territory, on May 10, 1869, signaling the end of an era… but the beginning of a legend.

General Store :

An 1800s general store was the heart of many small towns and rural communities—a place where people gathered not only to shop, but to catch up on news and connect with neighbors. The store was typically a wooden structure, multi-paned windows that displayed goods like bolts of fabric, tools, and canned goods to lure passersby. A hand-painted sign bearing the store’s name often hung above the entrance or on a swinging board.

Barrels and crates were scattered throughout the space, and a potbelly stove provided warmth in the colder months, doubling as a gathering spot for customers to linger and chat.

Tumbleweed Saloon:

The 1800s Tumbleweed Saloon captures the lively, rough-and-rowdy spirit of the Old West. As you step through the swinging batwing doors, you’re instantly transported to a time when cowboys, prospectors, and travelers sought refuge, refreshment, and revelry after long days on the trail. Just imagine the air feels thick with history, music, and the faint scent of whiskey and wood smoke.

A weathered upright piano stands in one corner, a nod to the tunes that once filled the room, played by saloon girls or wandering musicians. The main floor features replica poker tables straight out of the 1800s, complete with antique-style playing cards and even brothel tokens—small, historical curiosities that hint at the saloon’s colorful past.

The walls are adorned with authentic-style decor—everything from wanted posters and oil lamps to vintage rifles and portraits, all items that would’ve been common in a real saloon of the time. Every detail, down to the worn “wood-look” floor and dusty corners, has been carefully crafted to reflect life in the Old West.

Blacksmith Shop:

The 1800s Blacksmith Shop is a striking representation of one of the most vital trades in early American life. More than just a place to shoe horses, it was the beating heart of a growing community—where tools were forged, repairs were made, and innovation took shape in fire and iron.

We researched many photos and images of 1800’s blacksmith shops to design ours. Every detail was carefully chosen to reflect the authentic look and function of a working blacksmith shop from the 19th century. In addition, we had Amish blacksmiths assist in organizing the contents, ensuring that every tool, piece of equipment, and layout choice was rooted in time-honored knowledge and real-world experience.

Historians often refer to the first half of the 19th century as the “golden age” of American blacksmithing, when the demand for metalwork surged due to the growth of frontier towns and homesteads. Blacksmiths who could take on a wide range of specialized work were highly valued. The best smiths became “jacks of all trades,” able to fulfill the needs of farmers, builders, soldiers, and tradesmen alike.

If a tool didn’t exist for a particular job, a blacksmith would often make it himself. Over a lifetime, a blacksmith might amass hundreds of tools, many of which served a single, specialized purpose. Many such items are proudly displayed in our shop today, providing a glimpse into the ingenuity and adaptability that defined this crucial profession.

Whether you’re admiring the heavy forge, the unique hand-forged tools, or imagining the clang of hammer on iron, our blacksmith shop offers an unforgettable journey into the craftsmanship and labor that helped build early America.

Whiskey Still:

The 1800s Whiskey Still is a gritty, atmospheric glimpse into the world of early American distilling and backwoods bootlegging. Tucked away in a secluded corner that hints at secrecy and rebellion, this scene immerses visitors in the raw and rugged process of whiskey-making during a time when stills were often hidden from the law.

Feel what it must have been like in the 1800s to make whiskey and be a bootlegger. Surrounded by barrels, copper coils, and the scent of mash in the air, you’re transported to a time when whiskey wasn’t just a drink—it was currency, culture, and, for some, a calling. In rural communities, where cash was scarce and laws were looser, homemade whiskey was often a way of life. It fueled gatherings, warmed cold nights, and occasionally sparked trouble with the taxman.

Our proprietor is lounging in a chair watching over his still, a sly smile on his face and a jug by his side. His posture is relaxed, but his eyes are sharp—he knows that while the fire is hot and the copper is bubbling, he’s walking the line between craftsman and outlaw. His world is one of hidden trails, whispered deals, and careful measurements, where every batch could bring either celebration or consequences.

This exhibit offers more than a visual—it’s a moment frozen in time that invites you to imagine the risk, reward, and resilience of those who lived by their wits and distilled with their hands. Whether for profit or passion, the whiskey still was a symbol of frontier spirit and fierce independence.

Post Office:

An 1800s post office was a small but essential hub of communication, often tucked inside a general store, a stand-alone wooden building, or even part of someone’s home in rural towns. Though modest in size, it was a place buzzing with anticipation, community news, and the hope of faraway connections.

Behind that counter, the postmaster—often a well-respected figure in the community—handled letters, newspapers, and parcels. He or she would use a hand-cranked cancellation stamp, log deliveries in thick ledgers, and prepare mailbags for the next coach or horseback rider. In some locations, the mail arrived via stagecoach, while in more remote areas, it came by horseback through the Pony Express or local couriers.

Though small and simple, the 1800s post office was a lifeline—a place that connected the scattered dots of the growing nation, one letter at a time.

U.S. Marshals Office:

An 1800s U.S. Marshal’s office was a no-nonsense, multifunctional space that served as the lawman’s headquarters, a public deterrent to crime, and often the first stop for anyone caught breaking the law. Usually located near the center of town—often right beside a bank or post office—it was a modest wooden building, typically marked with a hand-painted “Marshal” sign and maybe a star on the door.

On the walls were wanted posters, notices of town meetings, and occasionally a bulletin board with rewards or warnings. A small stove or fireplace provided heat in the colder months, and a cracked window might be propped open in summer to let in some breeze—or the distant sounds of the town.

The Marhsal’s role went far beyond just enforcing the law—he was also the town’s peacekeeper, investigator, and sometimes even the judge in minor disputes. Whether facing down outlaws, keeping the peace at community events, or tracking a stolen horse, the Marshal operated from this simple but essential stronghold of law and order.

Though humble in size, the 1800s Marshall’s office symbolized justice, authority, and the strength of a growing American town determined to keep order on the frontier.

Jail:

An 1800s jail was a stark and rugged place—more about confinement than comfort, designed to keep lawbreakers under lock and key in a time when justice was swift and often local. Usually built near the town center, the jail was a small, squat building made of thick timber or rough-hewn stone, with iron bars on the windows and a heavy wooden door reinforced with metal straps.

Lighting came from kerosene lamps or small windows set high in the walls—just enough to cast long, moody shadows across the floor. The floors were often packed dirt or uneven stone, and heating was minimal, if present at all. In colder regions, a small potbelly stove might sit in the corner of the main room, but its warmth rarely reached the cells.

While simple by modern standards, these early jails were a powerful symbol of law and order on the frontier—a clear message that even in the most remote towns, justice had a home.

Bank:

An 1800s bank was a symbol of progress and prosperity in a growing frontier town—a place where gold, currency, and trust changed hands daily. Typically built from brick or sturdy timber, the bank stood out from the simpler wooden storefronts around it, often featuring large front windows, a bold sign overhead reading “BANK,” and occasionally an American flag fluttering outside to convey authority and legitimacy.

The back of the bank housed the vault—a thick iron safe or reinforced room with a heavy door and a complex locking system for the time. Inside were gold coins, silver bars, currency notes, and personal lockboxes for customers. Because robbery was a very real risk, banks often had armed guards, and many were located near the sheriff’s office for extra security.

The atmosphere was quiet, serious, and businesslike. The furniture was solid—dark-stained wood desks, chairs, and sometimes a cast iron stove in the corner. On the walls, you might see maps of the local territory, current or past President(s), framed documents, or the latest exchange rates for gold and silver.

In many towns, the bank represented hope—a place where dreams of owning land, building a business, or saving for the future could become reality. But it also came with tension, especially during hard times, when trust in the system could waver and a locked vault might be the only thing standing between stability and chaos.

The Chuck Wagon:

Our Chuck Wagon is a full-size, roadworthy replica of a true American icon—built to honor the rugged ingenuity of the Old West and the vital role this mobile kitchen played on the open trail.

A Cowboy’s Kitchen and Lifeline on the Trail

The very first chuck wagon rolled onto the plains in 1866, crafted by legendary rancher and trailblazer Colonel Charles Goodnight, co-founder of the famed Goodnight-Loving Trail. At a time when Texas cattle drives were booming and cowboys were in high demand, Goodnight recognized that keeping a trail crew well-fed—and morale high—was key to success. His solution? A fully outfitted mobile kitchen strong enough to withstand the grueling conditions of thousand-mile cattle drives.

Contrary to popular belief, chuck wagons weren’t part of every pioneer caravan. They were purpose-built for Texas cowboys driving massive herds northward to railheads and markets. With cowboy labor scarce and competition fierce, Goodnight’s innovation helped him recruit the best hands in the business—by promising something rare on the trail: hot, hearty meals.

From War Wagon to Trail Legend:

From War Wagon to Trail Legend:

Goodnight’s original design started with a sturdy army-surplus Studebaker wagon, built with steel axles and heavy-duty wheels tough enough for rough terrain. With the help of a trusted cook, he transformed it into a compact and efficient rolling kitchen. The heart of the wagon was the “chuck box”, a slanted, hinged cabinet at the rear that folded down to form a prep table. Inside, it housed drawers, shelves, and cubbies for cooking tools, spices, beans, bacon, and everything needed to feed hungry trail hands.

Beneath the chuck box was the “boot”, perfect for storing large, heavy items like the essential cast-iron Dutch oven. Outside the wagon, a water barrel and coffee grinder were mounted, while a canvas or rawhide “possum belly” swung below to carry firewood and dried cow chips for fuel. The wagon’s arched canvas top, held by wooden bows, kept supplies dry in all weather. Some wagons even featured a “jockey box” in front to store tools and heavy gear, while a pull-out fly (awning) provided shelter from the rain during meal prep.

The chuck wagon didn’t just carry food—it hauled bedrolls, medicine, ropes, tools, horse feed, and the crew’s personal gear. It served as the cook’s domain, the crew’s dining hall, and a central hub for life on the dusty trail.

Our Tribute to a Western Icon

The chuck wagon you see here is a finely crafted, fully functional tribute to Charles Goodnight’s original design. Built primarily of oak or pine and iron, it carries all the distinctive features of a true trail wagon—from the chuck box to the water barrel, to the period-style gear and luggage it hauls. Every detail tells a story of grit, innovation, and the enduring spirit of the American cowboy.

It wasn’t just a kitchen on wheels—it was survival, comfort, and community rolled into one. And it remains one of the most iconic symbols of the cattle drive era.

Ponds

Gazebo

Designed with elegance and versatility in mind, the gazebo serves as the perfect setting for a wide variety of intimate and memorable moments.

From golden hour photo shoots to twilight ceremonies under the stars, this charming space brings a storybook atmosphere to your special day. Whether decorated with florals, soft draping, or left to shine in its simple, graceful form, the gazebo is a beloved feature of The Friesian Empire—inviting love, celebration, and unforgettable memories.

- Photo booth

- Photo opportunities

- Stage Coach

- Chuck Wagon

- Kitchen prep area

- Bride & Groom Suites

- Bridal House (~5,200SF

- Log home at the front of

- the property)

- Golf Carts

- Bar

- Describe each stall

- Parking

- Grounds features 2

- ponds, woods, pastures

- Carriage Rides

- Sleigh Rides

- Horse Barn tour

- Security patrol

From War Wagon to Trail Legend:

From War Wagon to Trail Legend: